We file into the red velvet seats of the wood and gold-colored theatre on Royal Caribbean’s Freedom of the Seas cruise ship. It’s day three of the third annual JoCo Cruise Crazy, and I’m excited to see today’s performer, cellist Zoë Keating. I had heard some of her music online, and in the television show Elementary, and I look forward to seeing her live. I have no idea what’s in store.

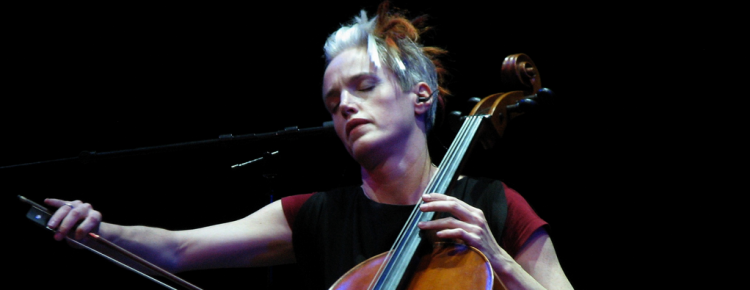

Keating’s look is unique. Like all concert cellists, she wears a black dress, but knee-length, with red peek-a-boo sleeves. Wicked, square whirlpool-patterned stockings cover her thin legs. Her stark white hair is extremely short, perhaps growing out from a shag-rug shave, and bright red dreadlocks sprout from the left side.“Everything that you hear is live, there’s no pre-recorded stuff,” they tell us during Keating’s introduction, and I have to continually remind myself during the performance. Keating produces such a rich, full sound, it’s hard to believe she is playing solo, just she and her cello—and a computer.

According to her bio, Keating “combines the cello and a foot-controlled computer, developing her signature style of live-layered music.” Using a looping technique, she builds fully composed, complex, and haunting pieces. She and her one instrument produce a sound worthy of a full orchestra.But more than that, Keating experiments with the instrument and the various sounds it can make. She is clearly a formally trained musician, yet she explores every facet of her instrument, no longer shackled to its dimensions as dictated by classical music conventions. Rather than playing Bach or Mozart or other brilliant classical composers, she decides to see just where she can take it and how far she can go. She investigates sound, technique, and ability, varying her touch and her stroke. She pulls it apart and reconstructs it, creating something completely new.

Some of the sounds seem like they were once accidents; those little scrapes and gaffes that musicians generally work to avoid in order to play “properly.” Instead, Keating uses them to create incredible symphonic paintings. Sometimes playing the strings pizzicato, sometimes using long, lush bow strokes. Sliding her left fingers along the fingerboard to smear the sound, eliding and smudging the strings. Combining smooth and lyrical with choppy and staccato. Varying the softness or firmness of the bow on the strings, fluctuating between lighter, scratchy sounds and deep, foreboding tones. It is truly haunting.

In addition, she has many ways of creating percussive rhythm: drumming her fingers on one side of the cello, and hitting her bow against the other side. Bouncing the bow on the strings, to add timbre to the choppy percussion. Striking the fingerboard as if brushing dirt off it. Tapping it gently with one finger, varying the note slightly. Even flicking the bridge between her thumb and forefingers. These all add texture to the already complicated pieces.

While creating these unique sounds, she presses buttons on the floor with her right foot, using the computer to loop and overlay her sounds. She plays call and response with the computer. Her action pauses but the sounds don’t. She listens momentarily to what she’s made so far, then creates a new sound to add to the tapestry. Sounds disappear and reappear, sometimes with a corresponding foot movement, sometimes without. The audience is left wondering how she possibly makes all of these sounds, and all within our presence. It doesn’t seem possible.

As a result, her works are probably never played the same way twice. For example, she explains that her piece “The Path” bears absolutely no resemblance to the one on the album. Each piece is “a picture frozen in time,” that she eventually lets go, and they become something else and “take other life forms,” to the point where she needs to rename them.

It’s not surprising that her music appears in television shows and films. It is very cinematic; her pieces are symphonic poems that draw clear pictures. She weaves a tapestry of sounds both strange and familiar, embroidering a distinctive image.

Keating’s stage presence is unassuming, but genuine; she seems uncomfortable or even embarrassed about what she can do, and would clearly prefer not to talk to the audience. It’s clear she does not make music for fame or recognition, but because she loves it. She is deeply entranced in her music, closing her eyes and swaying, allowing her music to move her body, and permitting her body movement to influence her music.

Though Keating uses a computer to enhance her music, it doesn’t sound electronic or computerized. An electric sound is only noticeable in her piece “Optimist,” which she wrote shortly before the birth of her son. “Optimist” begins with a tremolo, created by quickly and lightly moving the bow back and forth across the strings, rapid fire, which becomes the underpinning of the piece. By the end, she uses the computer to distort the sound, turning it into an electronic, synthesized, almost staticky sound, like an 8-bit chiptune from a video game.

By the time she reaches her penultimate piece, “Lost,” I truly am. I am overwhelmed by the preceding 45 minutes, pondering what Keating did and everything it means. My mother is a cellist, so I’ve always had an affinity for the instrument, but this is something I have never seen or heard. It becomes a metaphor for exploring everything in life and living life to the fullest, despite what others may say or history may dictate. I am completely overtaken with my thoughts while still allowing the sounds to radiate through me, until I find tears in my eyes.

Keating tells us that she started playing cello when she was eight, but “it took a long time to figure out that playing with a computer was the way to go.” While she sheds no light on how it came to her or how she does it, it is clear that she figured it out. And makes the most of it.

Passenger Jason Roop filmed this concert and posted it on his YouTube page. It’s reposted here with his permission.